What did your career path look like before taking your current role?

I studied physics in Edinburgh and came away with a master’s degree and a PHD in musical acoustics, before going into industrial engineering. My first role was a part of the production team at Coherent as a laser systems engineer and later a laser development engineer.

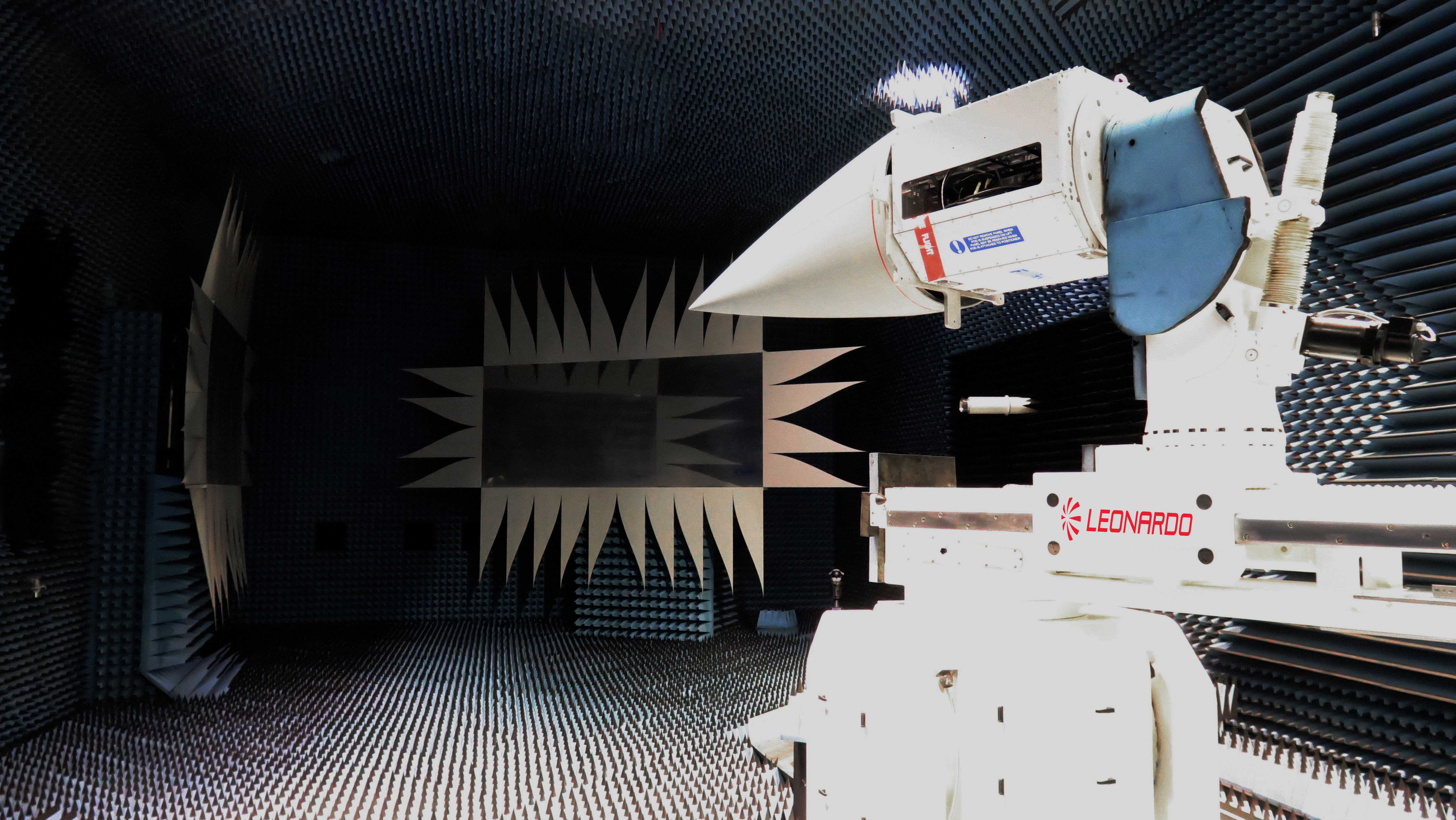

Given my academic background, the natural path into Leonardo, which was SELEX Galileo when I joined in 2012, was in the radar modelling team. I got to work on most of the company’s fire control radar projects and gained a lot of experience and knowledge which led me to take the opportunity that came up in 2020 which is my current role.

What are the fundamentals of the job?

It comes with a lot of different responsibilities, a primary one being my role as a technical point of contact between the team in Edinburgh and our customer(s), both in terms of purchasers of the system and the UK Ministry of Defence.

As Chief Systems Engineer, there are of course engineering fundamentals to the job, but my role is mainly about communication - establishing what the system requirements are and then helping Leonardo’s technical specialists to understand what that means for them.

Our customers are very keen to know how we are progressing and that we are going to meet the milestones and technical performance that they want to achieve. There is also pressure from within Leonardo – the ECRS Mk II radar is one of the biggest projects we’ve ever had so it is really important for us to deliver a successful product.

Despite the pressure, what attracted you to the job?

Being honest, as a physicist I kind of fell into my post-university career. However, I soon learned that I loved the tangibility of engineering. It also wasn’t long before I realised that working with advanced technology was a big thing for me.

With radar, one of the things I like is that I always feel like I’m learning. Radar systems are complicated, but each individual element is understandable - so there’s always something new to get to grips with. Radar science and acoustic science share some concepts so my background in music helped me in the early days.

Radar projects are interesting. The programmes are years long and you’re constantly hopping from one topic to the next, trying to keep everything moving.

Are there any individuals that standout as an inspiration to you, throughout your career?

The ones that spring to mind are the people who were a big part of my development when I first joined SELEX: Paul Rose and David Greig. They both taught me a lot on a technical level and gave me a good foundation within the business: who to speak to about different topics, the engineering, and the practical side.

It was their guidance that helped me forge an interest in radar and encouraged me to take a lead on customer engagement, which really inspired me to push on in my career. Paul was a former RAF engineer, so he helped put the importance of the role we play into perspective for me.

What are the non-negotiable skills required to succeed in your field?

When you bring it back to the basics it is an engineering job, so it is all the fundamentals of engineering: logical thinking, an ability to abstract problems between systems, the ability to think on your feet and pick up new things quickly.

Being able to pivot between topics with the relevant experts is vital, supported by good communication skills, the ability to extract key bits of information, and explain problems.

A really underrated skill for engineering is knowing whose expertise to seek. You’ve got to be able to recognise that, in Systems particularly, you need a lot of expertise from a lot of different people and knowing where to look is vital – we are surrounded by experts, so not being afraid to say, ‘I don’t know the answer to that, but I’ll find out’, is important.

Are there any particular challenges that are unique to your field?

The main challenge is the complexity of the task. With the ECRS Mk II radar, we are building an advanced radar system within an ambitious time frame – it is a real technical challenge.

Pressure comes from all sides, which adds to the challenge. The project is important for a huge number of people, both within Leonardo and externally, that earn their livelihoods from the project. Ultimately, however, we know that there’s a pilot in a Typhoon with a Mark II on the front that they will rely on it – the pressure of that makes it all feel very real.

How does it feel to be a part of the wider Eurofighter family?

It’s quite exciting, especially for a science ‘geek’. We’re all working on real cutting-edge technology and doing large scale engineering, so it is really interesting. I also like the multi-national aspect of it – nations working together is an important thing we facilitate and finally, for me, personally, military aviation is fascinating.

It ticks a lot of boxes for me in terms of personal and social interest, but it is a different environment that a lot of people don’t get to experience.

What does a typical day look like for you?

It’s a bit of a cliché but every day is different, though, of course, there are elements that are the same. Some days I can be supporting workshops or having technical discussions with the customer, others I can be reviewing documents or producing requirements.

I am a technical point of contact for our programme management so I’m in regular contact with them to establish where we are with development, what the timescales are like, whether we will meet our milestones. Some days are in the office, some are off site with customers, but the standard facet of any day is discussions.

How do you keep a work-life balance?

I have always been a keen musician – I listen to a lot of music, but I play as well, I was in orchestras when I was at university playing flute, now I mainly play bass and guitar.

When I was a student, I got really into korfball. Two teams of four men and four women try to put a ball through a basket – it is like a hybrid of basketball and netball, and is the world’s only mixed-sex sport. It’s a Dutch game so it’s not hugely popular in the UK but I love it.

I’ve been involved with various committees which has allowed me to travel a lot working with international groups, so it is a great sport to be a part of.

What advice would you give to your younger self?

That it is okay to not know the answer. It is better to go and find the answer than bluster through something. It comes with my job of corralling experts so I can find the answer if I don’t know it, I just have to decide where to look.